In the fight against flower, foliar and fruit diseases in almonds, there are key components growers need to be aware of as they decide what strategy fits best in the battle to protect their investment.

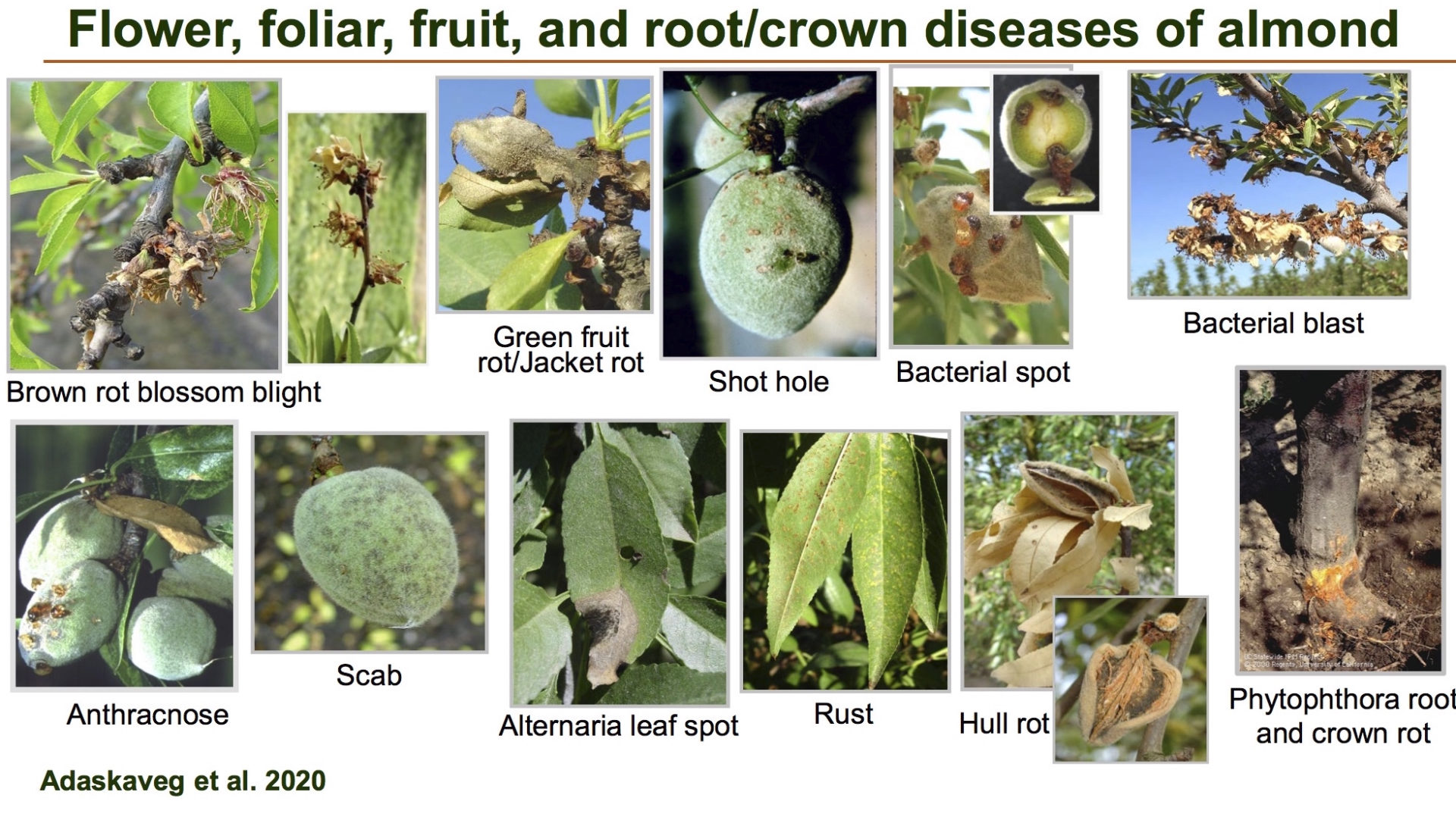

First growers must know what disease they are up against, Dr. James E. Adaskaveg, professor and plant pathologist at UC Riverside told a group of growers at the North Valley Nut Conference. Spring and summer foliar, flower and fruit diseases include brown rot blossom blight, scab, rust, green fruit rot/jacket rot, shot hole, anthracnose, bacterial spot, bacterial blast, alternaria leaf spot, hull rot, or phytopthora root and crown rot. Once the problem is identified, growers can best decide how to best manage the problem.

Adaskaveg explained that for a disease to become a problem it has to have all components of disease triangle: 1) The host, which is the cultivar, its physiology, growth pattern, and disease susceptibility; 2) The environment and its climatic and micro-climatic conditions, such as temperature, wetness, irrigation programs, air movement and wind; and 3) The pathogen, which might not be in the orchard at the start, but then gets introduced by being blown in by the wind, coming in from adjacent fields, or during planting.

“You have to have all three components of the triangle in order to get foliar disease into an orchard, and that is the critical thing to remember,” Adaskaveg said. “In addition, interactions between the components affect the amount of the disease and its spread.”

He added that environmental and host components of the triangle can give clues to which pathogens may be encountered, such as temperature and wetness, phenological stage of the host, host cultivar and presence of inoculum from previous seasons.

There are initial tools a grower can use in disease management, including the choice of tree variety, planting designs, irrigation systems and other practices. However, once these decisions are made and implemented, the orchard is what it is from that point forward, Adaskaveg said, and once disease is introduced into that orchard the grower has to look at other tool options.

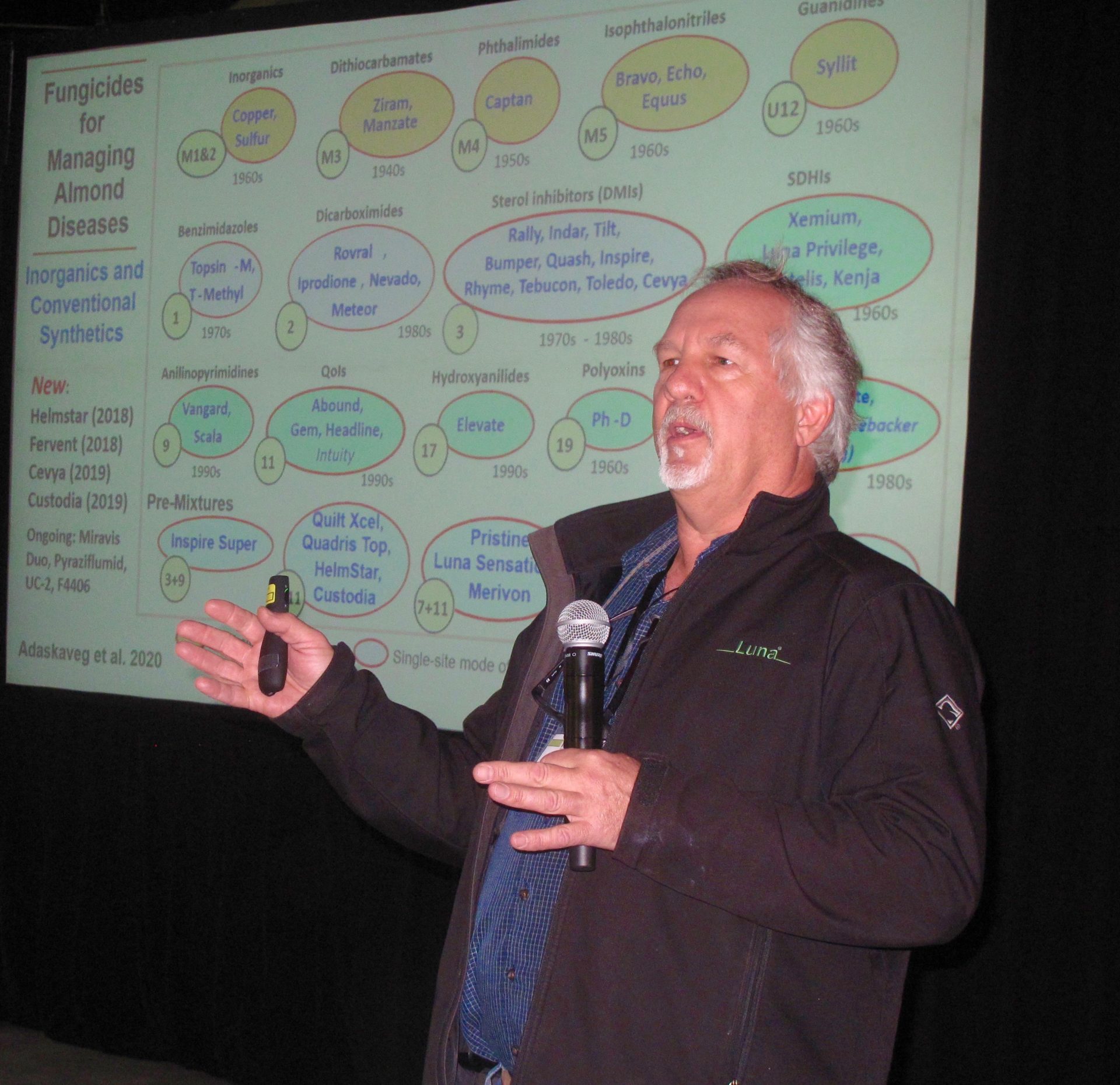

Adaskaveg said there are an increasing number of fungicides being introduced to the market, and some in ongoing development, with many of the new developments being pre-mixtures.

Generally, Adaskaveg said, all of the new reduced-risk fungicides do not affect bees.

He gives the following cautions concerning fungicide applications and the health of bees:

- Fungicides applied at bloom should not be mixed with adjuvants, such as penetrants, spreaders, stickers nor tank-mixed with insecticides, or fertilizers.

- Avoid bloom application of older multi-use fungicides such as chlorothalonil, Captan, and iprodione.

- Apply treatments to trees when bees are in the hive and not in flight (when temperatures are below 55 degrees F). Do not spray near hives.

- Apply fungicides after daily pollen release is exhausted (late afternoon, evening, or night).

- Follow UC guidelines for fungicide applications – delayed bloom applications under low disease pressure; two-bloom applications under high disease pressure; follow the “rules” for fungicide resistance management.

Brown Rot Blossom Blight

“Brown rot blossom blight, many growers know this disease well,” Adaskaveg said. “Prevention is the best way to manage this disease. Try not to ever let this disease get established in an orchard because to get rid of it with our minimal pruning practices is very difficult.”

Brown rot infection period is well-defined as the bloom period of seven to 14 days for each variety in the orchard. Risk of infection is determined by environmental conditions, such as temperature and wetness. There are varietal differences in susceptibility (Nonpareil the least susceptible) and those varieties need to be treated accordingly.

The disease spores are airborne and disseminated by wind or wind-driven rain, Adaskaveg said.

Wetness from rain, fog or dew allows germination within hours and infection when temperatures are between 64 to 77 degrees F. Because these conditions commonly occur each year during bloom, risk of disease is usually present, he added.

Green Fruit Rot/Jacket Rot

Green fruit rot/jacket rot comes in varieties of Botrytis cinerea (gray mold), Monilinia spp. (brown rot) and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, and is associated with the latter part of the bloom period when the fungus infects senescent blossom tissue.

Secondary infections can occur in jacket rot when infected petals fall onto leaves.

Infection in anthers can spread and spread from both petal and anther infection can result in damage to nut clusters.

Shot Hole

Shot hole of almond is a fungus that primarily infects leaves, fruit and green shoots, but rarely stems. Adaskaveg said shot hole infections are rare on traditional almond varieties, but common on some newer ones.

“With shot hole, when you get into trouble is when the infection occurs at bloom-time when the leaves are just coming out and they are small, and if infected they drop and even the fruit can drop, so it can be an economic problem disease like brown rot or jacket rot,” Adaskaveg said.

There are a number of “best treatment” fungicides for each of the diseases, including those used as single application at delayed bloom when environmental conditions are less favorable for infection.

Adaskaveg recommends the use of pre-mixtures for highest efficacy, consistency, and resistance management.

Also included among the best treatments are the biologicals.

Determining factors in choosing a fungicide include environmental conditions, such as rainfall, and fungicidal properties.

“Timing of bloom applications is based on host phenology and environmental conditions,” Adaskaveg said.

One of the goals in the treatment of these diseases is to use each class of fungicide only once per season or rotate between pre-mixtures containing different classes.

Adaskaveg provides the following advice on fungicide application:

- Many of the newer brown rot fungicides have some locally systemic activity and subsequent pre- and some post-infection activity.

- During less favorable environments, a single application at delayed bloom (20- to 40-percent bloom) is sufficient for good disease control.

- During highly favorable conditions, a two-spray program with applications at pink bud and full bloom is recommended.

Bacterial Blast and Canker

Bacterial Blast and Canker are springtime diseases of many fruit tree crops, such as citrus, pome and stone fruits.

Symptoms of the blast phase of the pathogen, Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae, develop typically in early spring. The disease can be very destructive to flowers and spurs and has no fungal mycelium as is found in brown rot and jacket rot.

Canker phase symptoms of the disease develop typically in late winter and early spring on the tree’s truck and scaffold branches. It can be very destructive to trees two to eight years old. A sour smell is associated with canker which shows itself by necrotic flecks which often merge to form large cankers that do not extend below a graft union.

The bacterial blast and canker pathogen are a ubiquitous epiphyte of plants and is disseminated by rain to natural plant openings, Adaskaveg said.

The disease develops on trees weakened or stressed primarily from frost damage and nematode damage. Varieties Mariana 2624 and the peach/almond hybrids Hansen, Nickels, Cornerstone, Titan and Bright’s are more susceptible to the disease, but all cultivars of almond are susceptible to various degrees.

Adaskaveg said it is important for growers to maintain health and vigor of their trees to avoid bacterial blast and canker through nutrition, pre-plant fumigation, post-plant nematicides and removing die-back.

Laboratory studies have shown all strains of the pathogen are sensitive to kasugamycin, but less so to copper, he said.

In February the EPA accepted a Section 18 petition to allow the use of Kasumin (kasugamycin) to control bacterial blast and canker in almond. This action provides almond growers a significant tool in the arsenal against the disease and the damage it causes to trees and crop loss.

Kasumin is an antibiotic treatment that has a different mode of action compared to other antibiotics and breaks down to near zero levels within 30 days. In addition, Adaskaveg explained, it offers no worker safety issues, is virtually non-toxic to mammals and there is no concern of resistance in human/animal bacterial pathogens with plant use.

Hull Rot

Warm and humid summers can make almond orchards more susceptible to diseases such as hull rot, especially with current planting practices causing almond orchard canopies to be denser with less light penetration.

There are two major hull rot pathogens, Monilinia fructicola and Rhizopus stolonifer, with Aspergillus niger and Botrytis cinera occasionally causing the disease.

Adaskaveg said it is often difficult to determine the pathogen in the field.

“Fruit have to be incubated or isolations have to be done to identify the pathogen,” he added.

In surveys of 12 orchards in the last two years in Butte, Colusa, Sutter, San Joaquin, and Stanislaus counties, Rhizopus was found to be the predominant cause of hull rot in 11 of the orchards. Aspergillus was found in one orchard in Stanislaus County at a low incident, Adaskaveg reported.

Inoculum of both Rhizopus and Monilinia are air-born, with Rhizopus found in soil and Monilinia originating from almond and other stone fruit.

Hull rot infects fruit and causes dieback, and is most severe under high humidity conditions in the orchard.

Timing of fungicide application for management is different for each of the two main pathogens.

For Rhizopus hull rot, early hull split applications when susceptibility is high should be done as the pathogen generally infects senescent tissues. Fungicides are applied most effectively with navel orangeworm applications. For Monilinia hull rot, applications should be done earlier, in late spring. Adaskaveg said fungicides, alkaline fertilizers, and, potentially, bio-controls can reduce the incidence of hull rot, as does planting, irrigation, sanitation and pruning practices.