Make electricity from almonds trees? Convert almond wood waste into a biopesticide? Those are intriguing business plans put forth by two new companies that aim to remove wood, shells and hulls from the waste stream and put them to beneficial use.

Eric McAfee of Aemetis Inc., a renewable fuels and biochemical company, and Mike Woelk of Corigin Solutions LLC, an organic ag solutions company, laid out the science and the business plans for their technology endeavors at an Almond Industry Conference session in December. Their common goal is to divert wood waste and end open burning of orchard waste.

Aemetis is using new technologies to produce advanced fuels as replacements for traditional petroleum-based products. They are converting first-generation ethanol and biodiesel plants into advanced bio refineries to produce zero emission fuels which also reduce carbon impacts of transportation.

Energy from solar, wind, hydroelectric and nuclear all reduce emissions of greenhouse gases compared to coal and petroleum, McAfee said, but these energy sources do not consume carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Plants used as feedstock for biofuels and biogas consume CO2 as they grow, allowing greenhouse gases to be reduced by use of biofuels McAfee said he is a big fan of electric vehicles, but “are we making electricity from coal or almonds?”

The renewable fuel production proposed by Aemetis will come from waste plant material that has consumed carbon dioxide during its life span and can achieve true progress in reversing climate change.

According to the California Air Resources Board’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard, biofuels lead in carbon reduction in California. Ethanol, McAfee said, is cleaner burning than gasoline and its use in vehicles reduces air pollution. Ethanol, which is 34 percent oxygen by weight, burns cleaner than gasoline by adding oxygen to engine combustion. Ethanol fuel cells can be used as generators to power electric motors for pickups, vans and trucks.

Aemetis will source the more than 2 million tons of ag waste produced annually in the Central Valley when unproductive orchards are removed as well as other woody waste to produce cellulosic ethanol, The amount of wood waste from orchard removals has been increasing as many biomass-to-electricity plants close due to competition from lower cost solar and wind generated power. Burning waste wood has increased since 2012, a UC Feedstock study has concluded, due to the closing of those plants.

The UC study confirmed that air emissions assumptions for carbon intensity score under the Low Carbon Fuel Standard. It also confirmed biomass growth and availability tonnage, identified feedstock pricing and feedstock projected cost for 20 years as supply increases due to foreign demand for almonds.

There are approximately 1.5 million acres of almond and walnut orchards in California. With an average production life of 20 years for almond trees, there are about 40,000 acres of trees removed annually providing about 1.6 million tons of orchard wood waste per year. Adding in pistachio shells and hulls, California orchards can support the production of 160 million cellulosic ethanol gallons per year at a conversion rate of 100 gallons per ton of wood waste. Cellulosic ethanol production would also create 30,000 direct and indirect jobs in the Central Valley, attract capital investment and eliminate open burning of wood waste.

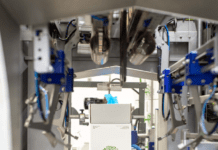

Aemetis, McAfee said, is building the first biomass to ethanol plant using a Lanzatech process that involves a proprietary microbe in the fermentation process. The integrated demonstration unit has already been completed and operated for 120 days. Aemetis has a signed 55-year lease on a 140-acre former U.S. Army ammunition production plant near Modesto. The site has additional space for expansion and waste wood feedstock storage area adjacent to plant. The plant will be 100 percent powered by hydroelectric energy.

The business has USDA loan approval for $125 million. In addition, the environmental assessment of the plant is complete and Aemetis has signed a 20-year feedstock contract and completed Ethanol Off-Take contracts and process engineering. Detailed engineering work is ongoing. Plans for the future include expansion to four plants in California with capability of 160 million gallons.

Corigin’s figures show that in 2020, the almond industry in California will produce 857,000 tons of shells, 924,000 tons of hulls, 2 million tons of trees, and 3.8 million tons of orchard waste.

“There is value locked in the waste stream that could be more valuable than the kernels,” Woelk said at The Almond Conference.

That waste, Woelk said, could be converted into $3.8 billion worth of biochemicals, biocarbons and bio-oils. In the process, 3.8 million tons of carbon dioxide could potentially be sequestered because the manufacturing process is carbon-negative. Such carbon offsets could be sold at $20 to $30 per ton or whatever the market supports.

Corigin’s process converts 2,000 pounds of almond shells into 1,600 pounds of product. That includes 600 pounds (75 gallons) of biodistillate, a plant growth stimulant, 600 pounds of the soil amendment biochar, 400 pounds of bio-oils (55 gallons) and volatiles, as well as biogas as an energy source to sustain the process.

The biodistillate process, Woelk explained, produces phenolics which are a natural defense mechanism for plants. The Corigin product Coriphol, made from almond shells, has been approved as an organic plant growth enhancer by OMRI and the California Department of Food and Agriculture. There is potential for such biodistillates to eventually be used as a natural pesticide. A recent USDA Agricultural Research Service study found Coriphol repels navel orangeworm at hull split and Asian citrus psyllids from citrus trees.

A Corigin biochar product made from almond shells, Corichar, is an approved organic soil amendment. Woelk reported it was tested in an almond orchard where it improved yields and reduced water use. Woelk also commented on the potential of biochar as a livestock feed additive to reduce methane emissions, and improve animal health and growth rates. From a carbon sequestration standpoint, Woelk explained that one ton of biochar is equivalent to three tons of carbon dioxide. But unlike other forms of CO2-equivalents, Corichar is a tangible product that is shipped in sacks adding a level of credibility to buyers of carbon offsets.

Woelk said that Corigin aims to build a highly scalable business with initial capacity of 3,200 tons of biomass with a maximum capacity of 20,000 tons. The plan is to prove the economic model at the Merced plant and then build additional plants in California and North America.

Production is scheduled to begin May 2020 at the site in Merced. Corigin has already been granted OMRI and CDFA regulatory approval for their flagship products and permits have been filed with the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District.

Dr. Karen Lapsley, Chief Scientific Officer at the Almond Board of California, moderator of the conference session, said the California almond industry is committed to finding higher value, optimal uses of almond co-products, noting that doing so is integral to the orchard of the future.

“Through the Almond Board’s biomass research program, we’re bringing groups together – groups that haven’t worked together before – to think differently, innovate and generate value,” Lapsley said. “It’s not just about being responsible with everything the orchard produces. It’s about looking for new and innovative uses for food products that may solve potential issues or provide benefits elsewhere.”