Now is the time to scout and monitor spider mites in both walnuts and almonds as warm weather continues throughout California. One way to do this, according to Emily Symmes, former UCCE Sacramento Valley area integrated pest management advisor, is to examine 10 leaflets from 10 trees (five should be from higher branches), weekly May through August. If more than half the leaflets with spider mites don’t also have predators (predaceous mites and/or sixspotted thrips), this is cause for concern. A scouting form is available at http://ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/C881/walnut-mitemon.pdf.

Spider mites, also called webspinning mites, are the most common mite pests in California nut orchards. Although there are a variety of spider mites, there is little need to distinguish one from the other since their damage, biology, and management are virtually the same.

To the naked eye, spider mites look like tiny, moving dots. They live in colonies, a single colony containing hundreds of mites, mostly on the undersurfaces of leaves. The presence of webbing is an easy way to distinguish them from all other types of mites and small insects such as aphids and thrips, which can also infest leaf undersides.

Sixspotted Thrips

One of the most effective, and cost-effective, ways to fight spider mites is with biological control, such as predator mites and sixspotted thrips, Symmes said. Other technics include cultural practices and miticide applications when needed.

Symmes said growers need to use biological control to their advantage by knowing what natural enemies are out there.

“Do this through scouting and monitoring,” she added. “Also, choose the least hazardous materials to the natural enemies and minimize risk through treatment timing, coverage and providing refuges.”

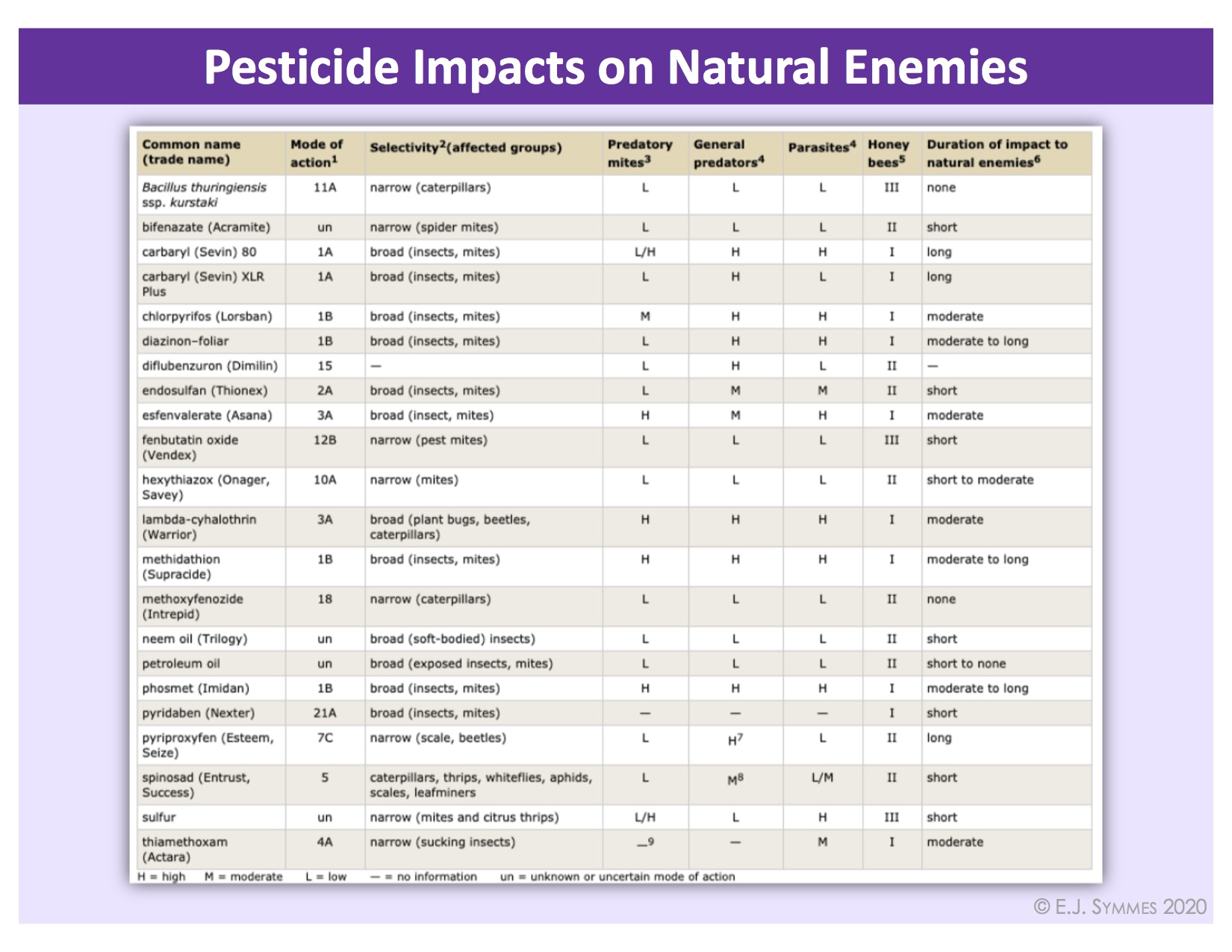

Avoid broad-spectrum pesticides (e.g., pyrethroids and organophosphates) at critical times of natural enemy population surge during the season. Symmes offers a graph (see Table 1) that provides a listing of pesticides and their impacts on bees and natural enemies.

“Why should the sixspotted thrips be your new best friend?” Symmes asked.

Here is why:

- They feed almost exclusively on spider mites.

- They thrive in hot dry climates.

- They are thigmotaxic (not afraid of tight spaces, thrive in mite webbing).

- They can eat 50 mite eggs per day at 86 degrees.

- They experience rapid population increase (can quadruple in one week).

- They are out there and they are free.

Don’t Starve them, Don’t Kill Them

If predators are present in the orchard and have some food to eat, such as spider mites, they will stick around and the numbers of beneficials will increase.

“This means that we have to be willing to tolerate some level of food source in the orchard to maintain predator populations. Food sources may come in the form of other mite species early in the season, as well as sub-economic populations of spider mites themselves throughout the season,” Symmes said.

Monitoring for the sixspotted thrips can be done with thrips sticky strip cards.

“Thrips card monitoring is better at sixspotted thrips detection than leaf counts,” according to results from Sacramento Valley almond and walnut 2019 studies, she added.

Spider Mite Treatment Thresholds

In general, the goal is to manage the ratio of predators-to-spider mites (not just spider mite numbers alone) to achieve a balance in which predators can provide free control services.

When using sixspotted thrips cards, 2.6 thrips on a card per week for every one mite on a leaf equals no change in mites seven days later, according to Symmes, citing a 2017 study by UCCE Entomology Advisor David Haviland in Kern County.

From mid-season to hull split, if a grower has 25 to 33 percent spider mite infested leaves with three thrips on a trap per week, he is breaking even with 50-percent chance mites will be the same or lower in 14 days. If there are six thrips on a trap per week, that is good news, and the grower should see 73-percent chance mites will decrease in seven days and 97-percent chance mites will decrease in two weeks.

With this method, Symmes says spider mites are treated once economic thresholds are reached (not before) and the overall goal is to maintain a balanced ratio of natural enemies-to-spider mites that will allow the beneficials to help suppress spider mite populations.

She shares the following guidelines:

- Monitoring and treatment thresholds take into account the abundance of both the pest spider mites and their key natural enemies (predator mites and sixspotted thrips).

- Early season destruction of natural enemies and/or their food sources will likely mean that they will not be present, or not present in enough numbers at the right time, to provide measurable impacts later in the season when growers need them to help fight flare-ups.

- Predators alone may not be sufficient to keep spider mites below economically damaging levels, and miticides may be needed based on site-specific monitoring of treatment thresholds. Know which predators are present and choose materials accordingly. Using a miticide that is softer on beneficials helps keep them around to suppress spider mites missed by the pesticide.

- Best practices for getting the most out of threshold-based miticide application include choosing the right material for the job (i.e., those softer on predators if they are present, desired residual activity and pre-harvest intervals, quick and effective knock-down if needed, etc.), obtaining optimal coverage (high volume, slow speed), and applying with oil or the recommended adjuvant.

Timely Miticides

Symmes said managing spider mites in almonds in recent years have typically taken one of two general approaches in conventional orchards: applying a prophylactic early-season treatment or utilizing threshold-based treatment timings (later season) and conserving biological control. Both have pros and cons, and each method can be used to successfully manage spider mites. Which is “better” depends on a number of factors in the particular orchard operation, the typical abundance of natural enemies and how effectively they are conserved and may vary depending on the environmental conditions year-to-year.

According to Haviland, there are a variety of miticides to choose from, with the key factor to miticide efficacy being how it applied. He said a slow, steady application provides the best results.

With a successful biocontrol threshold in place, growers have found they can reduce their use of sprays, and if the ratio of enemies to spider mites is balanced, eliminate sprays for spider mites altogether.

Symmes said early abamectin treatments (May), once a popular option in many almond orchards, seem to be waning over the past few seasons. Growers and PCAs are increasingly reporting concerns about efficacy and resistance-management considerations. When applied properly and at the appropriate time based on spider mite populations, abamectin can be an effective miticide and these early treatments can control mites into summer.

Following are some key considerations Symmes provides regarding the most effective use of abamectin:

- Abamectin functions as a nerve toxin that must be ingested by mites. Once applied, the material must move into the leaf tissue, where it can then be picked up by feeding mites. This translaminar movement of the material works best prior to leaf hardening and when leaves are mostly free from dust and other residues. Applications before leaf hardening can be quite effective.

- Applying abamectin after leaf hardening (i.e., with hull-split sprays) may seem like an inexpensive insurance policy, even if the effectiveness of the material at this timing is greatly reduced. However, bear in mind two additional issues: this is the time when natural enemies tend to be more abundant if preserved early in the season and, from a resistance-management standpoint, two applications of the same active ingredient within the same season is not advisable.

- Abamectin is highly toxic to spider mite natural enemies, particularly sixspotted thrips and predator mites. Use of abamectin early in the season may contribute to later season spider mite flare-ups due to reduction or elimination of these beneficials in the orchard by direct toxicity and/or by reducing their food source (spider mites, European red mites, brown almond mites.)

- Without beneficials to at least slow a mite flare up as the abamectin wears off (expect 60 days of activity if applied properly and at the tight time,) spider mite populations can jump to damaging levels in just a couple of weeks with summer heat and water stress.

- In years when spider mites are slow(er) to develop, “May sprays” of abamectin may be of very little value, as additional later season sprays often become necessary regardless of early-season intervention, and natural enemies are unnecessarily disrupted. Weigh the pros and cons of the inexpensive insurance policy in treating below-threshold populations vs. destruction of natural enemies and consider how overuse of a particular chemistry over time can increase the likelihood of resistance development. Best to use practices that help maintain all of the tools in the toolbox so that they are available and effective when particular situations call for it.

Avoid Prophylactic Approach

Avoid applying prophylactic spider mite treatments before economic thresholds are reached, Symmes advises.

UC IPM guidelines suggest the following treatment thresholds based on whether pyrethroid or organophosphates applied to target other pests have been or will be used this season: In orchards where pyrethroid or organophosphate applications are not used, consider treatment if samples show 30 to 40 percent spider-mite infested leaflets and predators on less than 10 percent of the leaflets or 40 to 50 percent spider-mite infested leaflets and predators on 20 to 50 percent of the leaflets. No treatment is warranted if predators are on 50 percent or more of the leaflets. In orchards where pyrethroid or organophosphate applications are used, consider treatment if samples show 10 percent spider-mite infested leaflets and predator mites on less than 10 percent of the leaflets or 20 percent spider-mite infested leaflets and predators on more than 10 percent of the leaflets.

Monitoring for the presence and absence of mite pests and natural predators, paying attention to treatment thresholds, and applying selective chemistry to maintain beneficial populations, make up an effective, and cost-effective, season-long approach for managing mites in nut orchards.