Aphid infestation and damage to pecans has become worse in the past five to six years.

Mild Winters

Larry Blackwell, New Mexico State University researcher and program coordinator College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, said that pecan producers in New Mexico are dealing with higher aphid numbers in their pecan orchards due to lack of freezing winter temperatures in recent years.

“We have had really mild winters and thus no kill off,” said Blackwell. The high numbers of aphids in pecans is the result of the climate, and not just due to population build up, Blackwell added.

This year blackmargined aphid population pressure for the first summer peak in the Mesilla Valley of southern New Mexico was high for what should be an off or lower yield year. Blackwell said pressure built in mid-May, approximately two weeks earlier than normal and populations declined at the end of June. This six-week period was unusually long for an off year where peaks in the summer typically last two to three weeks. Likely causes are a warm spring and a relatively heavy off-year crop.

Species of Aphid

There are two distinct species of aphid that cause damage in pecan production. The yellow pecan aphid complex consists of the yellow pecan aphid (Monelliopsis pecanisis) and blackmargined pecan aphid (Monellia caryella). Both are found throughout the US pecan growing belt.

The black pecan aphid is a completely different species than the yellow pecan aphid complex. The damage done to pecan crops by each species is different.

The black pecan aphid is the only black colored aphid that damages pecan foliage. According to the University of California Integrated Pest Management guidelines, the feeding of the black pecan aphid on pecan leaves causes bright yellow, angular quarter-inch spots to appear on the leaves between the veins. Leaf damage and subsequent defoliation affects both nut quality and crop yields the following year.

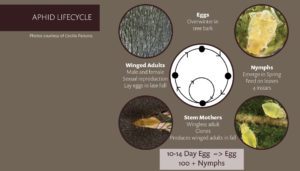

The black pecan aphid is pear-shaped and may be winged. Nymphs are dark green and may also be winged. The populations begin to build in spring and increase rapidly in August and September.

The yellow pecan aphid complex includes the blackmargined aphid and the yellow pecan aphid. The Blackmargined aphid has a black stripe along the outside margin of its wings, which are held flat over the body. The yellow pecan aphid lacks the black stripe along the wing margin and holds its wings in a peak over its body. Immature aphids are difficult to identify because they lack wings.

Yellow pecan aphids that have been parasitized will turn black and can be confused with black pecan aphids. However, the parasitized aphids are dead and stuck to the leaf surface. Live black pecan aphids will fly quickly when disturbed.

Both species of the yellow aphid have mouthparts that pierce and suck plant juices, removing water and plant nutrients from the leaves. As they feed, they excrete large amounts of honeydew, which collects on the leaves. Both species feed on the underside of leaves with the blackmargined aphid feeding on major leaflet veins while the yellow aphid feeds on the network of small veins throughout the leaflet.

Damage

This species does indirect damage to nut crops. Blackwell said until populations are very high, growers or pest control advisors who are scouting may not realize the crop damage caused by aphid feeding.

Yellow aphid eggs overwinter in bark crevices on tree trunks and branches. After hatching in the spring, the aphid feed on new leaf growth and in a short time give birth to live young—all females—which reproduce at a rapid rate as temperatures warm. This species is bi-modal with two population peaks, in June and again in September.

Infestation Rates

Blackwell noted the blackmargined aphids population peaks and infestation rates have trended upward since 2011. Not only are the pest densities higher, but the infestations begin earlier and last longer in the year. Peak population timing is close to historic dates, but numbers of blackmargined aphids per compound leaf have risen dramatically. In off years from 2012 to 2017, at the July 15-31 peak, counts were at 23 per leaf while historically, they were at 12. The September-October peak levels in 2017 were at 27 per compound leaf while historically they were at six.

Numbers during on years were also higher from 2012-2017. The early peak was one to two weeks later, but the numbers were up with 73 aphids per compound leaf compared to a historic rate of 43. In the September-October peak, numbers soared to 96 per compound leaf compared to the historic rate of 29.

The high numbers can have a significant impact on nut quality. During on years, there is an increased likelihood of a higher percentage of lower grade nuts. There is also a considerable reduction in blooming terminals and yield for the next growing season.

Blackwell said that control in past years has been mainly with contact insecticides though some contact /translaminar products were used. University of California (UC) integrated pest management (IPM) guidelines for control warn that insecticides do not consistently control either species of yellow aphid and they may become resistant if insecticides are not rotated.

With higher aphid numbers, Blackwell said that pecan growers are having to spray more than once during the season to achieve control. Because populations can quickly blow up scouting for infestations is important. Results are better, he said if spray applications start before higher numbers are found. The target is 10-20 per compound leaf. Numbers can climb rapidly and at that point sprays are basically rescuing the crop rather than protecting. If populations can be knocked back during the June peak, Blackwell said, the outlook for the second populations peak in September could be better.

Chemical Control

His control recommendations for the June peak is Closer, sulfoxaflor product with translaminar activity or Beleaf, a flonicamid product with translaminar activity. Sivanto or Movento are also good, he said. Closer and Beleaf both had higher mortality rates on blackmargined aphids in a 2013-2016 trial. Since these are systemic insecticides, Blackwell said they need time to distribute in the leaves because the product has to be ingested by the aphid to be effective. All four chemistries are from different IRAC classes. Blackwell said that rotation of classes of insecticides is critical as it will help with resistance management. Failing to rotate among the different classes will lead to resistance and reduce the number of products that are effective.

There can be performance inconsistencies with insecticides. Environmental factors including rain and humidity and wind can cause less of the product to be taken up by the plants. Timing is another critical factor in the aphid control success rate.

Achieving sufficient coverage of spray applications depends on tree architecture and canopy. Blackwell said there is evidence that a more concentrated solution can produce better results. Higher spray volumes are required with legacy products to achieve coverage of both sides of the leaves. Admire, Belief and Movento have label volume recommendations of 50 plus gallons per acre. There is no label volume recommendation for Closer.

Blackwell noted that surfactant use is needed to improve spray coverage. It may also improve initial spray deposits, redistribution and weatherability. He said there are very little statistically significant differences between surfactants. Any surfactant use is better than none, he said.