Excellent soils and a Mediterranean climate make California one of the most productive agricultural centers in the world, allowing the state to produce two-thirds of the nation’s fruits and nuts, and one-third of its vegetables. Reducing our production capability means in the future, we will be more dependent on global markets to supply the food products we currently grow here at home.

In 2018, the California Legislature passed Senate Bill 100, the “100% Clean Energy Act.” It sets a 2045 target date for supplying all retail electricity sold in California as well as state agency electricity needs with renewable and zero-carbon energy resources. This new electricity will come primarily from solar, which are expected to account for 81.1% of the total. But wind and a small amount from geothermal sources are also part of California’s carbon-free energy plan.

California will need to add about 70,000 megawatts of new commercial solar generation by 2045 to meet the legislative target. The California Energy Commission (CEC) says it requires between seven and 10 acres of solar to generate 1 megawatt of electricity, meaning the state will need 490,000 to 700,000 acres of land to achieve the goal.

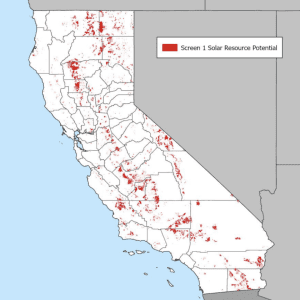

An October staff report to the state energy commission identified areas where solar cannot be built, including population centers, military installations, tribal lands and property set aside for environmental protection, mining or other uses. Much of the remaining allowable land for solar production remains in agricultural areas, including much of the Central Valley and the Salinas, Imperial and Palo Verde valleys.

That leaves many farmers and supporters of domestic food production wondering what the ultimate impact of this transition will be on California’s agriculture industry.

USDA says California lost 1 million acres of irrigated farmland between 1997 and 2017. After years of failures to build new state water storage infrastructure, another 1.2 million acres were fallowed in 2021 and 2022 due to drought and water shortages, according to UC Merced.

For generations, much of lost farmland has been attributed to urban or suburban development, a reality that will continue as the state’s population keeps growing. And now there is a significant new threat to farmlands: California’s desire to build a massive amount of new solar facilities.

There is significant interest in farmland that could be fallowed due to California’s 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act. In a recent report, the Public Policy Institute of California said, “In the San Joaquin Valley, this will likely mean taking more than 500,000 acres of agricultural land out of intensive irrigated production.” That is in addition to land already fallowed.

additional transmission lines for new solar development.

However, it is important to remember that much of the farmland expected to go out of production was at one time sustainably farmed using groundwater resources because adequate surface water supplies helped replenish the aquifer. As a result of periodic droughts, inadequate infrastructure and water policies limiting surface water deliveries, the last 30 years have contributed directly to current levels of overdraft.

California’s intent should be to build solar facilities on previously retired land and, if additional property is required, only use land that will be fallowed due to the state’s groundwater law. Otherwise, unless California finds a way to use solar development in some way to support its remaining agricultural land, who will grow the food that feeds much of America and the world?

California Energy Commission staff say they will make every effort to site new solar facilities on the least productive land possible. But solar facilities depend on transmission capabilities to move electricity from where it is generated to where it will be used. Existing transmission lines aren’t currently in all areas the CEC identified for potential solar development. That means there is a potential loss of higher-value farmland.

The CEC can work to minimize this by talking to local planners and agricultural advisors such as county agricultural commissioners and Cooperative Extension specialists. Those experts can provide valuable advice when decisions are being made on where to site new solar facilities.

California’s agricultural viability has been taken for granted far too long. In the future, we may wish we had taken better care of our farmland and the farmers who grow our food. We shouldn’t waste precious, dwindling agricultural acreage when there are few areas around the world that produce the quantity and variety of food products grown here in California.

Throughout California’s history, development has shaped the kind of state in which we live. Developing new sources of renewable energy is a good thing and deserves support. However, we shouldn’t try to fix our energy problem by creating an even bigger food problem.